An Honest Guide to Negotiating Working Capital in SaaS M&A

How the peg really works, how deferred revenue distorts it, and how to keep it fair.

Safety briefing, and my assumption of objections

This piece is practical guidance from my deal experience — not tax or legal advice. Any experienced PE colleague could debate exceptions, but this framework keeps negotiations straightforward and prices fair without unnecessary drama.

Why this matters

Sellers can lose money on a line they didn’t expect: the net working-capital (NWC) peg. It seems like an accounting detail, but in SaaS M&A, it’s often the loudest fight and the last thing discussed. I did a quick count, and I’ve now negotiated this over 30 times. That experience gap is where a seller’s blood pressure rises, as they worry about value leaks.

What the peg actually is

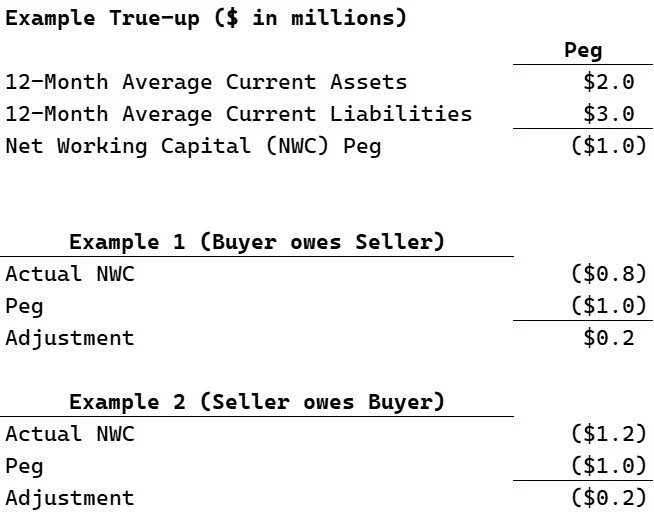

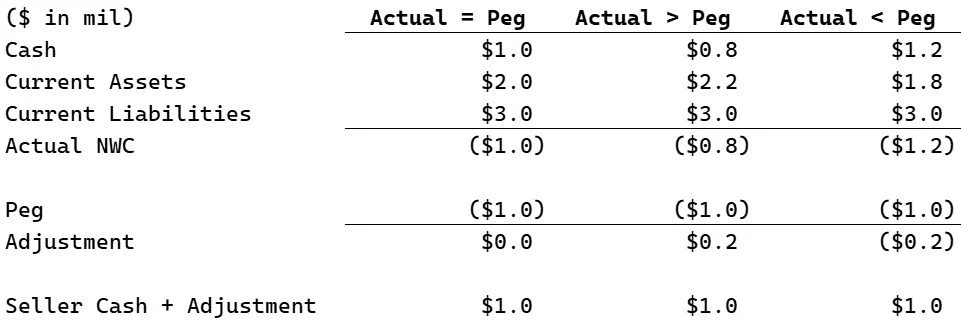

Before the tactics, it helps to define the battlefield. The peg is a target level of NWC you agree to deliver at close. After closing, there’s a true-up: if actual NWC is below the peg, the price ticks down; if it’s above, it ticks up. Agreeing on how to measure NWC (the methodology) matters more than arguing the number in the abstract.

Two early signals about your future partner

Timing and transparency tell you almost everything. Fair buyers include a working-capital methodology in the LOI and share a schedule, then and again after diligence, with final numbers. Buyers who punt the topic or keep the math hidden are usually setting up a late-stage squeeze.

SaaS balance sheets behave differently

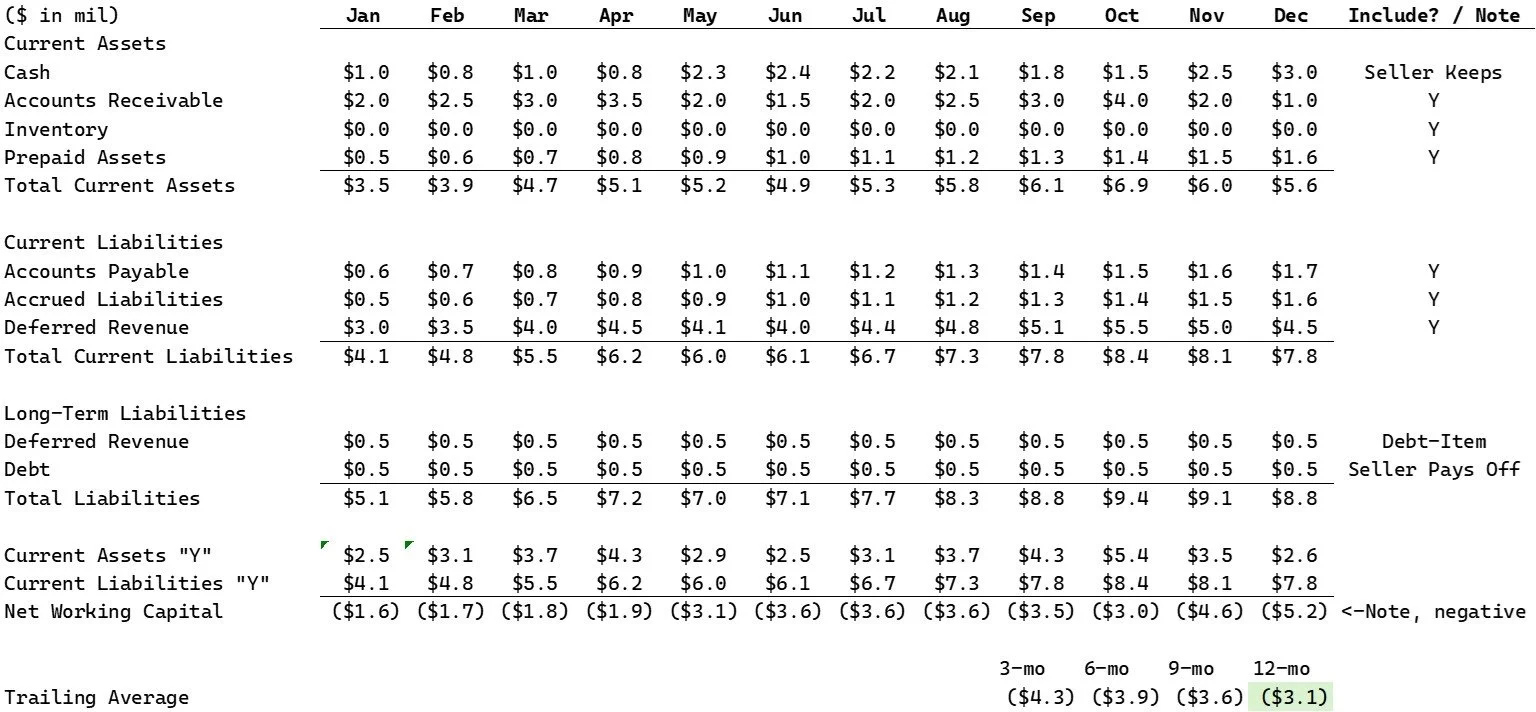

Annual, upfront invoicing means you collect cash before you deliver service. When you invoice, you record Cash or Accounts Receivable (A/R) and a Deferred Revenue liability; you recognize revenue over the subscription term. In a growing SaaS business, Deferred Revenue typically rises faster than it amortizes, so NWC is often negative and can trend more negative as you grow. That’s not a red flag; it’s a sign of growth, as you’re generating cash before delivering service.

Deferred revenue: the crux

Here’s a simple framework that avoids most drama:

Treat any long-term deferred revenue (months 13+) as debt, outside the peg. The seller keeps the cash, and the buyer keeps the obligation to deliver; pricing should reflect it.

Include short-term deferred revenue (next 12 months) inside NWC. Use the 12-month average when setting the peg.

Don’t count it twice. If an element sits in “debt-like items,” don’t let it also suppress NWC in the peg.

Setting a fair peg

Start with a full year. SaaS renewals and billing cycles create seasonality that shorter lookbacks miss. A 12-month average captures the rhythm of the business and prevents cherry-picking. Define what’s in current assets and liabilities, and agree on exclusions early.

An honest buyer should walk you through something like this at the LOI stage as you agree on the methodology. The action is in what’s included and excluded. Remember that you keep the cash, and the key is transparency up-front, and that the buyer calls out the NWC method they based the purchase price on.

A tiny example

Assume a business with a steady renewal season in Q1 and steady growth. Over the last 12 months, average current assets (cash excluded) are $2.0M, average current liabilities are $3.0M, driven by short-term deferred revenue. Average NWC is −$1.0M. That negative is normal for this billing model. Set the peg at −$1.0M. If closing-date NWC is −$0.8M, you’re $200K above the peg and recover that in the true-up. If it’s −$1.2M, expect a $200K reduction. Fairness lies in the methodology agreed up front, not in last-minute interpretations. See below for a more visual representation.

This is what a summary of actual NWC versus the peg may look like.

It is common to provide an estimate at closing, so the post-closing adjustments shouldn’t be huge unless your projections are way off, or if a buyer deploys tactics after the closing.

Common pressure tactics and how to defuse them

Buyers rarely say ‘we’re gaming you,’ but you’ll feel it when they shorten the lookback to 3–9 months to cherry-pick a number; re-classify routine accruals as “debt-like”; or say they’re “following GAAP” to exclude assets or increase liabilities. The antidote is the one-page schedule shared at LOI that fixes definitions and the averaging period, plus a sentence in the purchase agreement that ensures no double-counting. Post-closing, any mention of “normalization” warrants analysis, and ask the buyer to explain it in layman’s terms.

Peace of mind after closing

If there’s a post-closing adjustment, up or down, don’t view it as a “win” or a “loss” if you set the methodology fairly from the start. The math is simple: if you owe money after closing, it’s because you already collected and kept more cash. Maybe a big receivable came in right before closing, which is great, but it lowers your A/R balance and, therefore, your actual working capital against the peg.

If the opposite happens, and you have not collected the A/R, you don’t keep the cash, but your A/R stays higher, so your working capital measures higher, and you benefit against the peg.

This is overly simplified, but the point I’m making is if you do this right, the A/R is really what might swing the final adjustment, but as you keep the cash collected, you shouldn’t lose sleep over it.

Do ask about what accounts drive any variance. If it’s cash or A/R, that is a normal swing, but if it is something else, be mindful of write-offs, adjusted accruals or other accounting tricks. Ask questions and understand the why.

It always feels like a scorecard moment, but in reality, it’s the math doing its job, exactly as agreed back at the LOI. Try not to stress once that’s locked. A good buyer understands this too, even if a deal partner is egging on some poor VP to “win the peg.”

My rule of thumb

Price the deal assuming a fair, 12-month-average treatment that includes short-term deferred revenue in NWC and treats true long-term deferred revenue as debt. Then live by it. If you have to “win” working capital at the closing table, you probably mis-priced the business or picked the wrong partner.

Closing thought

How a buyer handles the peg is a personality test. If you see transparency and early alignment, you’ll likely get it elsewhere too. If you see games here, expect them in post-close adjustments, budgets, and boardrooms. Also, be aware of a newer archetype, the private equity principal that hides behind their third-party accountants. If they can’t explain it to you plainly, understand they’ve sent in their henchman. Choose accordingly.